While using my time tracking system, TagTime Web, I have on many occasions wanted to use some complex logic to select pings. My first implementation of this just had a simple way to include and exclude pings, but this later proved to be insufficent for my needs. I considered implementing a more complex system at first, but I decided it was a good idea to wait until the need actually arised before building a more complex system like this. Here, I will explain how I implemented this new system. Well, after using TagTime Web for a while, the need has arrised, at least for me, so I built such a query system.

Here are some example queries, each with different syntax, demonstrate the range of ways queries can be formulated:

- To find time I’m distracted on social media, I can use a query like

distracted and (hn or twitter or fb) - To find time I’m programming something other than TagTime Web, I can do

code & !ttw - To find time I’m using GitHub but not for programming or working on TagTime Web, I can do

gh AND !(code OR ttw)

My main goal with the query design was to make it very simple to understand how querying works – I didn’t want to make users read a long document before writing simple queries. I also wanted to write it in Rust, because I like Rust. It can be run in the browser via WebAssembly, and since I was running WASM in the browser already I wasn’t going to lose any more browser support than I already had. Rust is also pretty fast, which is a good thing, especially on devices with less computing power like phones (although I don’t think it made much of a difference in this case).

Let’s dive in to the code. You can follow along with the source code if you want, but note that I explain the code a bit differently than the order of the actual source code. There are three main phases in the system: lexing, parsing, and evaluation.

Lexing

In the lexing phase, we convert raw text to a series of tokens that are easier to deal with. In this phase, different syntaxical ways to write the same thing will be merged. For example, & and and will be repersented with the same token. Lexing won’t do any validation that the provided tokens are sensical though: this phase is completely fine with unmatched brackets and operators without inputs. Here’s what the interface is going to look like:

let tokens = lex("foo and !(bar | !baz)").unwrap();

assert_eq!(

tokens,

vec![

Token::Name { text: "foo".to_string() },

Token::BinaryOp(BinaryOp::And),

Token::Invert,

Token::OpenBracket,

Token::Name { text: "bar".to_string() },

Token::BinaryOp(BinaryOp::Or),

Token::Invert,

Token::Name { text: "baz".to_string() },

Token::CloseBracket

]

);

Let’s start implementing that. We’ll start by defining what a token is:

#[derive(Debug, Clone, PartialEq, Eq)]

enum Token {

OpenBracket,

CloseBracket,

Invert,

Name { text: String },

BinaryOp(BinaryOp),

}

Instead of having two different tokens for &/and and |/or, I’ve created a single BinaryOp token type, since the two types of tokens will be treated the same after the lexing phase. It’s just an enum with two variants, although I could easily add more if I decide so in the future:

#[derive(Debug, Copy, Clone, PartialEq, Eq)]

enum BinaryOp {

And,

Or,

}

I’ve also implemented a few helper methods: from_char, as_char, and from_text that will help with lexing. Now let’s get on to actually lexing. We’ll declare a fn that takes a &str and returns a Vec<Token>. We start out by defining the ParseState enum, inside lex:

fn lex(s: &str) -> Result<Vec<Token>, &'static str> {

#[derive(Debug, Copy, Clone, Eq, PartialEq)]

enum ParseState {

/// Ready for any tokens.

AnyExpected,

/// In a name.

InName,

/// In a binary operation repersented with symbols.

InSymbolBinOp(BinaryOp),

}

let mut state = ParseState::AnyExpected;

let mut tokens = Vec::new();

let mut cur_name = String::new();

Did you know that you can define an enum inside a fn? This is pretty neat: it allows you to define an enum that’s only available inside the fn that defined it, which helps prevent implementation details from being exposed and used in other places. We’ll use this throughout lexing to keep track of what we’re currently looking at. Next, we’ll break up the input string into individual UTF-8 characters, and loop over them:

for c in s.chars() {

Okay, time for the fun part: let’s build tokens out of these characters.

// the last token was "|" or "&", which has some special logic

if let ParseState::InSymbolBinOp(op) = state {

state = ParseState::AnyExpected; // only do this for the immediate next char

if c == op.as_char() {

// treat "|" and "||" the same way

continue;

}

}

if state == ParseState::InName {

let end_cur_token = match c {

// stop parsing a tag as soon as we see a character starting a operator

'(' | ')' | '!' => true,

_ if BinaryOp::from_char(c) != None => true,

_ if c.is_whitespace() => true, // whitespace also ends a tag

_ => false,

};

if end_cur_token {

let lower = cur_name.to_ascii_lowercase(); // tags are case insensitive

if let Some(op) = BinaryOp::from_text(&lower) {

// append the token

tokens.push(Token::BinaryOp(op));

} else {

// the token is "and" or "or", so treat it like a binary operation

tokens.push(Token::Name { text: cur_name });

}

cur_name = String::new(); // reset the current tag

state = ParseState::AnyExpected; // anything could occur next

} else {

// not ending the current token, so add this character to the current tag

cur_name.push(c);

}

}

// any token could happen!

if state == ParseState::AnyExpected {

let op = BinaryOp::from_char(c); // try to make a binary op out of the token

match c {

_ if op != None => {

// we managed to create a binary operation

tokens.push(Token::BinaryOp(op.unwrap()));

state = ParseState::InSymbolBinOp(op.unwrap());

}

// operators

'(' => tokens.push(Token::OpenBracket),

')' => tokens.push(Token::CloseBracket),

'!' => tokens.push(Token::Invert),

// ignore whitespace

_ if c.is_whitespace() => {}

// didn't start anything else, so we must be starting a tag

_ => {

state = ParseState::InName;

cur_name = String::with_capacity(1);

cur_name.push(c);

}

}

}

Finally, we check if there is any remaining tag tag info and return the tokens:

if !cur_name.is_empty() {

let lower = cur_name.to_ascii_lowercase();

if let Some(op) = BinaryOp::from_text(&lower) {

tokens.push(Token::BinaryOp(op));

} else {

tokens.push(Token::Name { text: cur_name });

}

}

tokens

Parsing

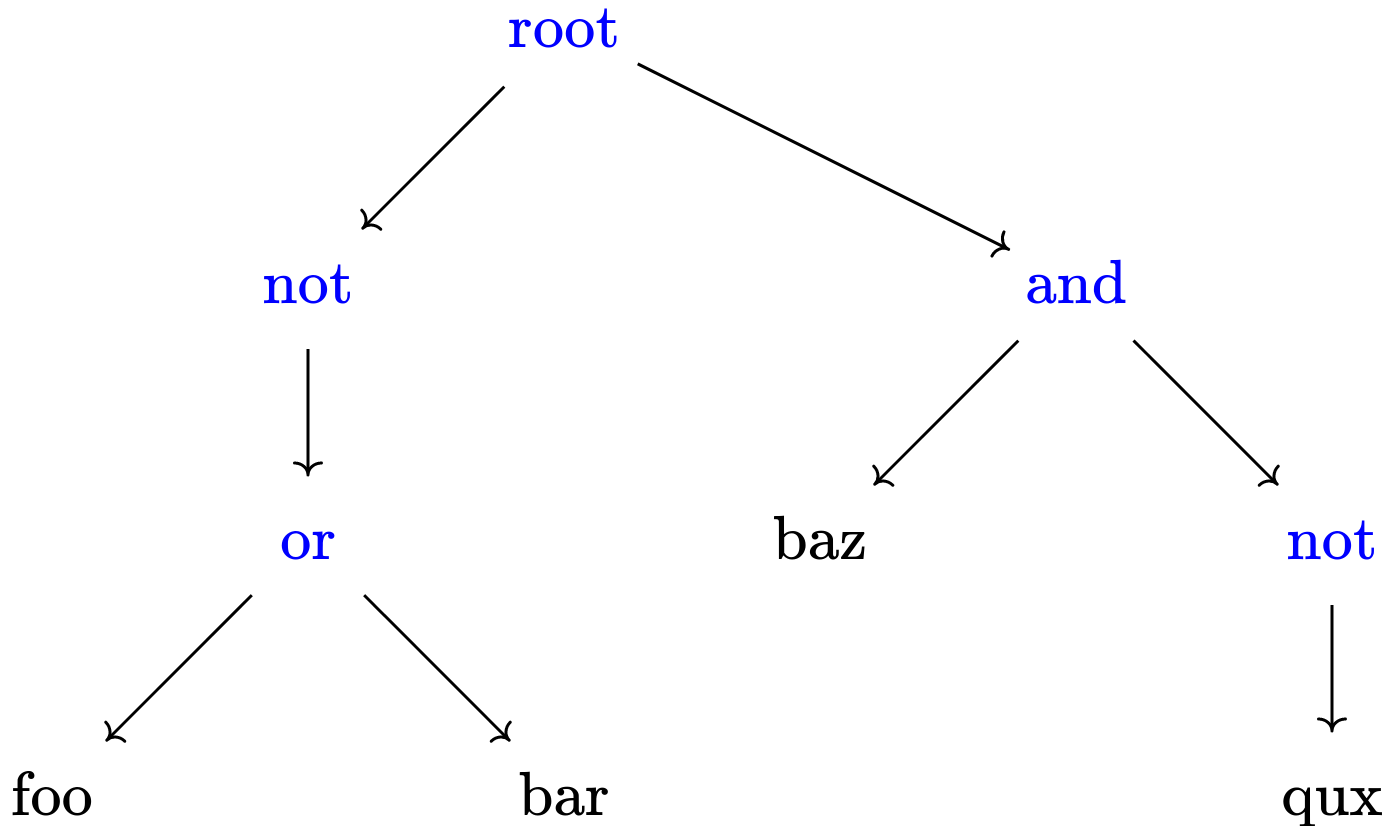

Here, we’ll take the stream of tokens and build it into an abstract syntax tree (AST). Here’s an example diagram (edit on quiver):

This will repersent the expression in a way that’s easy to evaluate. Here’s the definition:

#[derive(Debug, Clone, PartialEq, Eq)]

enum AstNode {

/// The `!` operator

Invert(Box<AstNode>),

/// A binary operation

Binary(BinaryOp, Box<AstNode>, Box<AstNode>),

/// A name

Name(String),

}

Munching tokens

Let’s implement the core of the parsing system that converts a stream of Token to a single AstNode (probably with more AstNodes nested). It’s called munch_tokens because it munches tokens until it’s done parsing the expression it sees. When it encounters brackets, it recursively evaluates the tokens in the brackets until it’s done with the stuff in brackets. If there are still tokens left after the top level call, then there are extra tokens at the end: an error. Here’s the declaration of munch_tokens:

impl AstNode {

fn munch_tokens(

tokens: &mut VecDeque<Token>,

depth: u16,

) -> Result<Self, &'static str> {

if depth == 0 {

return Err("expression too deep");

}

// ...

}

}

Notice that if there was an error doing parsing, a static string is returned. Most parsers would include more detailed information here about where the error occured, but to reduce complexity I haven’t implemented any such logic. Also note that the input is a VecDeque instead of a normal Vec, which will make it faster when we take tokens off the front often. I could also have implemented this by having the token input be reversed, and then manipulating the back of the token list, but it would make the code more complicated for fairly minimal performance gains. We also use depth to keep track of how deep we are going, and error if we get too deep to limit the amount of computation we do, since we might be evaulating an expression with untrusted user input.

Now let’s write the core token munching loop using a while let expression. We can’t use a normal for loop here, since the tokens will be mutated in the loop.

while let Some(next) = tokens.get(0) {

// ...

}

Err("unexpected end of expression")

Now for each token, we’ll match against it, and decide what to do. For some tokens, we can just error at that point.

match next {

// some tokens can't happen here

Token::CloseBracket => return Err("Unexpected closing bracket"),

Token::BinaryOp(_) => return Err("Unexpected binary operator"),

// ...

}

For tag names, we need to disambiguate between two cases: is the token being used by itself, or with a Boolean operator? When binary operators are between tokens we need to look ahead to figure out this context. If we were to use Reverse Polish Notation then we wouldn’t have this problem, but alas we are stuck with harder to parse infix notation. If the parser sees such amgiuity, it fixes it by adding implict opening and closing brackets, and trying again:

match next {

// <snip>

Token::Name { text } => {

// could be the start of the binary op or just a lone name

match tokens.get(1) {

Some(Token::BinaryOp(_)) => {

// convert to unambiguous form and try again

tokens.insert(1, Token::CloseBracket);

tokens.insert(0, Token::OpenBracket);

return Self::munch_tokens(tokens, depth - 1);

}

Some(Token::CloseBracket) | None => {

// lone token

let text = text.clone();

tokens.remove(0);

return Ok(AstNode::Name(text));

}

Some(_) => return Err("name followed by invalid token"),

}

}

}

Next, let’s implement opening brackets. We munch the tokens inside the bracket, remove the closing bracket, then do the same binary operation checks as with tag names.

match next {

// <snip>

Token::OpenBracket => {

tokens.remove(0); // open bracket

let result = Self::munch_tokens(tokens, depth - 1)?;

match tokens.remove(0) {

// remove closing bracket

Some(Token::CloseBracket) => {}

_ => return Err("expected closing bracket"),

};

// check for binary op afterwards

return match tokens.get(0) {

Some(Token::BinaryOp(op)) => {

let op = op.clone();

tokens.remove(0).unwrap(); // remove binary op

let ret = Ok(AstNode::Binary(

op,

Box::new(result),

Box::new(Self::munch_tokens(tokens, depth - 1)?),

));

ret

}

Some(Token::CloseBracket) | None => Ok(result),

Some(_) => Err("invald token after closing bracket"),

};

}

}

Okay, one operator left: the ! operator, which negates its contents. I’ve made the design decision not to allow expressions with double negatives like !!foo, since there’s no good reason to do that.

match next {

// <snip>

Token::Invert => {

tokens.remove(0);

// invert exactly the next token

// !a & b -> (!a) & b

match tokens.get(0) {

Some(Token::OpenBracket) => {

return Ok(AstNode::Invert(Box::new(Self::munch_tokens(

tokens,

depth - 1,

)?)));

}

Some(Token::Name { text }) => {

// is it like "!abc" or "!abc & xyz"

let inverted = AstNode::Invert(Box::new(AstNode::Name(text.clone())));

match tokens.get(1) {

Some(Token::BinaryOp(_)) => {

// "!abc & xyz"

// convert to unambiguous form and try again

tokens.insert(0, Token::OpenBracket);

tokens.insert(1, Token::Invert);

tokens.insert(2, Token::OpenBracket);

tokens.insert(4, Token::CloseBracket);

tokens.insert(5, Token::CloseBracket);

return Self::munch_tokens(tokens, depth - 1);

}

None | Some(Token::CloseBracket) => {

// "!abc"

tokens.remove(0); // remove name

return Ok(inverted);

}

Some(_) => return Err("invalid token after inverted name"),

}

}

Some(Token::Invert) => {

return Err("can't double invert, that would be pointless")

}

Some(_) => return Err("expected expression"),

None => return Err("expected token to invert, got EOF"),

}

}

}

Evaluation

Thanks to the way AstNode is written, evaluating AstNodes against some tags is really easy. By design, we can just recursively evaluate AST nodes.

impl AstNode {

fn matches(&self, tags: &[&str]) -> bool {

match self {

Self::Invert(inverted) => !inverted.matches(tags),

Self::Name(name) => tags.contains(&&**name),

Self::Binary(BinaryOp::And, a1, a2) => a1.matches(tags) && a2.matches(tags),

Self::Binary(BinaryOp::Or, a1, a2) => a1.matches(tags) || a2.matches(tags),

}

}

}

The only weird thing here is &&**name, which looks really weird but is the right combination of symbols needed to convert a &String to a &&str (it goes &String -> String -> str -> &str -> &&str).

Putting it all together

We don’t want to expose all of these implementation details to users. Let’s wrap all of this behind a struct that takes care of calling the lexer and building an AST for our users. If we decide to completly change our implementation in the future, nobody will know since we’ll have a very small API surface. There’s one more case we want to handle here: the empty input. AstNode can’t handle empty input, so we’ll implement that in our wrapper. This seems like it would work:

pub enum ExprData {

Empty,

HasNodes(AstNode),

}

But if you try that you’ll get a compile error.

error[E0446]: private type `AstNode` in public interface

--> src/lib.rs:16:14

|

8 | enum AstNode {

| ------------ `AstNode` declared as private

...

16 | HasNodes(AstNode),

| ^^^^^^^ can't leak private type

In Rust, data stored in enum variants are always implictly pub, so this wrapper would allow users access to internal implementation details, which we don’t want. We can work around that by wrapping our wrapper:

#[derive(Debug, Clone, PartialEq, Eq)]

enum ExprData {

Empty,

HasNodes(AstNode),

}

#[derive(Debug, Clone, PartialEq, Eq)]

pub struct Expr(ExprData);

Now let’s implement some public fns that wrap the underlying AstNode:

const MAX_RECURSION: u16 = 20;

impl Expr {

pub fn from_string(s: &str) -> Result<Self, &'static str> {

// lex and convert to a deque

let mut tokens: VecDeque<Token> = lex(s).into_iter().collect();

if tokens.is_empty() {

// no tokens

return Ok(Self(ExprData::Empty));

}

let ast = AstNode::munch_tokens(&mut tokens, MAX_RECURSION)?;

if !tokens.is_empty() {

return Err("expected EOF, found extra tokens");

}

Ok(Self(ExprData::HasNodes(ast)))

}

pub fn matches(&self, tags: &[&str]) -> bool {

match &self.0 {

ExprData::Empty => true,

ExprData::HasNodes(node) => node.matches(tags),

}

}

}

That’s it! If you want some more Boolean expression content, check out the test suite for some more moderately interesting tests.